John Carmack proposes fiber optic cache to replace DRAM for streaming AI model weights

3 Sources

3 Sources

[1]

John Carmack muses using a long fiber line as as an L2 cache for streaming AI data -- programmer imagines fiber as alternative to DRAM

Anybody can create an X account and speak their mind, but not all minds are worth listening to. When John Carmack tweets, though, folks tend to listen. His latest musings pertain using a protracted fiber loop as an L2 cache of sorts, to hold AI model weights for near-zero latency and gigantic bandwidth. Carmack came upon the idea after considering that single mode fiber speeds have reached 256 Tb/s, over a distance of 200 km. With some back-of-the-Doom-box math, he worked out that 32 GB of data are in the fiber cable itself at any one point. AI model weights can be accessed sequentially for inference, and almost so for training. Carmack's next logical step, then, is using the fiber loop as a data cache to keep the AI accelerator always fed. Just think of conventional RAM as just a buffer between SSDs and the data processor, and how to improve or outright eliminate it. The discussion spawned a substantial amount of replies, many from folks from high pay grades. Several pointed out that the concept in itself is akin to delay-line memory, harkening back to the middle of the century when mercury was used as a medium, and soundwaves as data. Mercury's mercurialness proved hard to work with, though, and Alan Turing himself proposed using a gin mix as a medium. The main real-world benefit of using a fiber line would actually be in power savings, as it takes a substantial amount of power to keep DRAM going, whereas managing light requires very little. Plus, light is predictable and easy to work with. Carmack notes that "fiber transmission may have a better growth trajectory than DRAM," but even disregarding plain logistics, 200 km of fiber are still likely to be pretty pricey. Some commenters remarked other limitations outside of the fact that Carmack's proposal would require a lot of fiber. Optical amplifiers and DSPs could eat into energy savings, and DRAM prices will have to come down at some point anyway. Some, like Elon Musk, even suggested vacuum as the medium (space lasers!), though the practicality of such a design would be iffy. Carmack's tweet alluded to the more practical approach of using existing flash memory chips, wiring enough of them together directly to the accelerators, with careful consideration for timing. That would naturally require a standard interface agreed upon by flash and AI accelerator makers, but given the insane investment in AI, that prospect doesn't seem far-fetched at all. Variations on that idea have actually been explored by several groups of scientists. Approaches include Behemoth from 2021, FlashGNN and FlashNeuron from 2021, and more recently, the Augmented Memory Grid. It's not hard to imagine that one or several of these will be put into practice, assuming they aren't already.

[2]

A cure for the memory crisis? John Carmack envisions fiber cables replacing RAM for AI usage, which would mean a better future for us all

While it's highly theoretical and a long way off, there are other possible nearer-term solutions to reduce AI's all-consuming appetite for RAM John Carmack has aired an idea to effectively use fiber cables as 'storage' rather than conventional RAM modules, which is a particularly intriguing vision of the future given the current memory crisis and all the havoc it's wreaking. Tom's Hardware noticed the cofounder of id Software's post on X where Carmack proposes that a very long fiber optic cable - and we're talking 200km long - could effectively fill in for system RAM, at least when working with AI models. Carmack observes: "256Tb/s data rates over 200km distance have been demonstrated on single-mode fiber optic, which works out to 32GB of data in flight, 'stored' in the fiber, with 32TB/s bandwidth. Neural network inference and training [AI] can have deterministic weight reference patterns, so it is amusing to consider a system with no DRAM, and weights continuously streamed into an L2 cache by a recycling fiber loop." What this means is that said length of fiber is a loop where the needed data (normally stored in RAM) is being "continuously streamed" and keeping the AI processor always fed (as the AI model weights can be accessed sequentially - this wouldn't work otherwise). This would be a very eco-friendly, power-saving way of completing these tasks, too, compared to traditional RAM. As Carmack points out, this is the "modern equivalent of the ancient mercury echo tube memories", or delay-line memory, where data is stored in waves going through a coil of wire. It's not an idea that's feasible now, but a concept for the future, as mentioned - and what Carmack is arguing is that it's a conceivable path forward which possibly has a "better growth trajectory" than we're currently looking at with traditional DRAM. There are very obvious problems with RAM right now in terms of supply and demand, with the latter far outstripping the former thanks to the rise of AI and the huge memory requirements therein. (Not just for servers in data centers that field the queries to popular AI models, but video RAM in AI accelerator boards, too.) So what Carmack is envisioning is a different way to operate with AI models that uses fiber lines instead. This could, in theory, leave the rest of us free to stop worrying about RAM costing a ridiculous amount of cash (or indeed a PC, or a graphics card, and the list goes on with the knock-on pricing effects of the memory crisis). The problem is that there are a lot of issues with such a fiber proposition, as Carmack acknowledges. That includes the sheer quantity of fiber needed and difficulties around maintaining the signal strength through the loop. However, there are other possibilities along these lines, and other people have been talking about similar concepts over the past few years. Carmack mentions: "Much more practically, you should be able to gang cheap flash memory together to provide almost any read bandwidth you require, as long as it is done a page at a time and pipelined well ahead. That should be viable for inference serving today if flash and accelerator vendors could agree on a high-speed interface." In other words, this is an army of cheap flash memory modules slapped together, working massively in parallel, but as Carmack notes, the key would be agreeing on an interface where these chips could work directly with the AI accelerator. This is an interesting nearer-term proposition, but one that relies on the relevant manufacturers (of AI GPUs and storage) getting their act together and hammering out a new system in this vein. The RAM crisis is forecast to last this year, and likely next year too, potentially dragging on for even longer than that with all sorts of pain involved for consumers. So, looking to alternative solutions for memory in terms of AI models could be a valuable pursuit towards ensuring this RAM crisis is the last such episode we have to suffer through.

[3]

John Carmack floats fiber delay-line cache to stream AI weights

John Carmack has a habit of tossing out ideas that sit right on the edge between practical engineering and pure provocation. His latest musing lands squarely in that zone: what if a long loop of optical fiber could act as a cache-like buffer for AI model weights, keeping accelerators fed by streaming data instead of leaning so heavily on DRAM? The core of the concept is "data in flight." Optical fiber has propagation delay, and at extremely high throughput that delay becomes measurable storage capacity. Using the example Carmack referenced -- 256 Tb/s transmission over roughly 200 km of single-mode fiber -- you can estimate how much data exists inside the cable at any moment. Multiply the bandwidth by the transit time and you end up with a payload on the order of tens of gigabytes, with Carmack's quick math landing around 32 GB. It's not memory in the conventional sense, because it's not addressable like DRAM. It's a delay line: a timed stream that comes out of the loop when it comes out, and can be recirculated to repeat a known sequence. The AI motivation is easy to understand. AI accelerators often hit a data movement wall before they hit a compute wall. If weight data could be supplied at very high bandwidth in a steady stream, you could design execution around predictable weight access rather than repeated fetches from large, power-hungry memory pools. Carmack's framing treats DRAM as a staging buffer between storage and compute and asks whether that staging layer could be reduced -- or redesigned -- if the accelerator can rely on a deterministic, high-throughput feed. Of course, a clever idea becomes a real system only after you pay for the details. Delay-line memory is an old concept historically used with acoustic media, and optical fiber inherits the same tradeoff: access is time-based, not random. That means it only works well if the workload can be scheduled to match the stream. Real AI deployments include variability in batching, kernel scheduling, framework behavior, and model architecture. Even if inference is often repetitive, "streaming-friendly" is not the same thing as "always sequential." Power and cost arguments are also complicated. Fiber doesn't require refresh the way DRAM does, and optical signaling can be efficient. But pushing extreme bandwidths over long distances typically requires transceivers, amplification, and DSP, and those subsystems can claw back energy savings. Then there's physical reality: hundreds of kilometers of fiber has to be packaged, routed, serviced, and integrated into a platform that data centers can actually operate. Carmack also points to a more grounded alternative that chases the same outcome: building large flash pools close to accelerators and defining standard interfaces and timing models so weights can be streamed directly with less dependence on DRAM. Variants of that approach already exist in research, and it fits neatly with the industry trend of rethinking memory hierarchies for AI at scale. In other words, the fiber loop "cache" may never ship as a product, but it lands a useful punch: if the bottleneck is feeding compute, future systems may look less like classic PCs and more like carefully scheduled, bandwidth-first pipelines. Source: Tom's Hardware

Share

Share

Copy Link

John Carmack, cofounder of id Software, has proposed using 200km fiber optic loops as a cache alternative to traditional DRAM for AI workloads. The concept leverages 256 Tb/s data rates to keep 32GB of data continuously streaming to AI accelerators, potentially offering significant power savings and addressing the ongoing memory crisis affecting AI development and consumer hardware costs.

John Carmack Envisions Radical Shift in AI Memory Architecture

John Carmack, the legendary cofounder of id Software and creator of Doom, has sparked intense discussion in the tech community with a provocative proposal: using long fiber optic lines as a cache system for streaming AI model weights, effectively replacing traditional DRAM in certain AI workloads

1

. The concept addresses a critical challenge as AI accelerators increasingly hit data movement bottlenecks before reaching their computational limits.

Source: Tom's Hardware

Carmack's fiber optic cache idea centers on "data in flight" — leveraging the propagation delay in optical fiber as functional storage capacity

3

. With single-mode fiber achieving 256 Tb/s data rates over 200km distances, his calculations reveal that approximately 32GB of data exists within the cable at any given moment, with a staggering 32TB/s bandwidth1

. This creates what he describes as a recycling fiber loop that could continuously stream data into an L2 cache, keeping AI accelerators constantly fed without relying on power-hungry DRAM.

Source: TechRadar

Delay-Line Memory Concept Returns for Modern AI Challenges

The proposal represents a modern revival of delay-line memory, a technology dating back to mid-20th century computing when mercury was used as a medium and soundwaves carried data

1

. Alan Turing himself once proposed using a gin mixture as an alternative medium. The concept works for AI because model weights can be accessed sequentially for inference and nearly so for training, making deterministic weight reference patterns possible2

.The primary advantage lies in power savings. Maintaining DRAM requires substantial energy for constant refresh cycles, while managing light through fiber demands far less power

1

. Carmack suggests that "fiber transmission may have a better growth trajectory than DRAM," a particularly relevant observation given the ongoing memory crisis2

. However, optical amplifiers and Digital Signal Processors (DSPs) could partially offset these energy gains.Practical Hurdles and Near-Term Alternatives

While theoretically compelling, the fiber optic cache faces significant implementation challenges. The sheer logistics of managing 200km of fiber, maintaining signal strength throughout the loop, and the considerable cost present immediate obstacles

2

. More fundamentally, the system only functions when workloads match the stream timing. Real AI deployments involve variability in batching, kernel scheduling, and model architecture that complicate purely sequential access patterns3

.Recognizing these limitations, Carmack also highlighted a more practical near-term solution: ganging flash memory chips together to provide massive read bandwidth, as long as operations are done a page at a time and carefully pipelined

1

. This approach would require flash and AI accelerator vendors to agree on a high-speed interface, but given the massive investment in AI infrastructure, such standardization appears feasible2

.Related Stories

Research Already Exploring Similar Memory Architectures

Variations on these concepts have already been explored in academic research. Projects including Behemoth from 2021, FlashGNN and FlashNeuron from the same year, and more recently the Augmented Memory Grid have investigated alternative memory architectures for AI workloads

1

. These approaches align with industry trends toward rethinking memory hierarchies specifically for AI at scale, moving away from traditional PC-like architectures toward bandwidth-first pipelines3

.The timing of Carmack's proposal matters. The memory crisis, driven by AI's insatiable appetite for RAM, has created supply shortages that inflate costs for consumers purchasing everything from graphics cards to complete systems

2

. If AI workloads could be shifted to alternative memory solutions, it would relieve pressure on traditional DRAM markets. The crisis is forecast to persist through this year and potentially beyond, making alternative approaches increasingly attractive.Whether fiber loops become practical datacenter components remains uncertain. But Carmack's thought experiment underscores a critical point: as AI accelerators grow more powerful, feeding them data efficiently becomes the limiting factor. Future systems may prioritize predictable, high-throughput streaming over random access flexibility, fundamentally changing how we architect AI memory systems. The conversation his proposal sparked — drawing responses from industry leaders and researchers — suggests the tech community recognizes that conventional memory hierarchies may not scale indefinitely for AI workloads. Watch for continued experimentation with flash-based solutions and new interface standards that could materialize sooner than exotic fiber configurations.

References

Summarized by

Navi

[1]

Related Stories

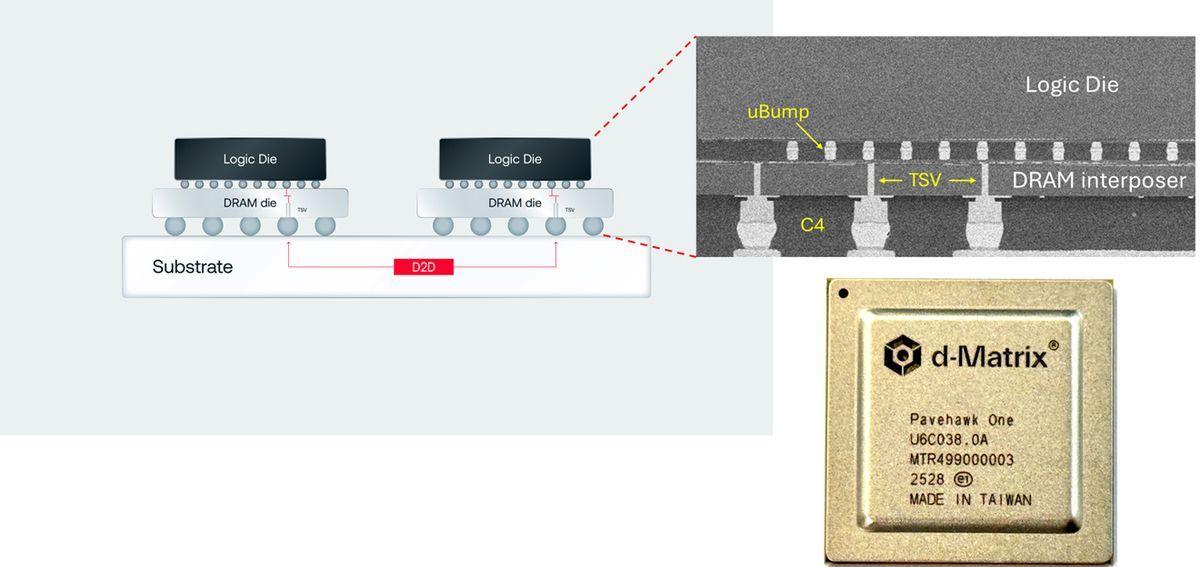

D-Matrix Challenges HBM with 3DIMC: A New Memory Technology for AI Inference

04 Sept 2025•Technology

DRAM shortage could last until 2028 as AI boom reshapes memory market and drives prices up 90%

Yesterday•Business and Economy

NVIDIA Unveils Futuristic Vision for AI Compute: Silicon Photonics and 3D Stacking

11 Dec 2024•Technology

Recent Highlights

1

Anthropic releases Claude Opus 4.6 as AI model advances rattle software stocks and cybersecurity

Technology

2

University of Michigan's Prima AI model reads brain MRI scans in seconds with 97.5% accuracy

Science and Research

3

UNICEF Demands Global Crackdown on AI-Generated Child Abuse as 1.2 Million Kids Victimized

Policy and Regulation